Sunday, 12 September 2010

...when he was fifteen...

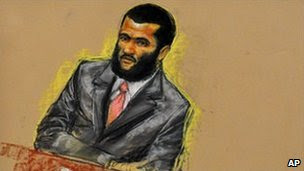

A former child combatant has gone on trial at Guantanamo Bay, the first detainee to face military justice under President Barack Obama.

A former child combatant has gone on trial at Guantanamo Bay, the first detainee to face military justice under President Barack Obama.

As it happens always when it comes to war-related events, we tend to focus on the horror of crimes, the horror if war, and not focus on the reasons why those events took place, or the things that were actually going wrong during the course of the conflict. I would like to point out something I find even more essential, than the actual murder being discussed here. The underlying fact that must be considered is: Why are kids sent to war? In my opinion, we cannot expect a child to be fully aware of the extent in the consequences (immediate or not) of his actions... That's why they are called "adolescents" remember? It comes from the Latin, and means "to be lacking of...". Lacking of maturity, which is not wrong at all, it is a stage of life that should be respected as they all are.

Sunday, 5 September 2010

77 Million Paintings

Brian Eno discusses 77 Million Paintings, which sees the continued evolution of his exploration into light as an artist’s medium and the aesthetic possibilities of “generative software.”

77 Million Enos

Some weeks ago the exposition called 77 Million Paintings by Brian Eno closed at a museum we all know in Mexico City. I was there, sat there for, seriously, about two hours and contemplated the installations trying not to even blink!

Some weeks ago the exposition called 77 Million Paintings by Brian Eno closed at a museum we all know in Mexico City. I was there, sat there for, seriously, about two hours and contemplated the installations trying not to even blink!The question I raise now is, Was It Art? I mean, Brian Eno is a British artist devoted to everything that can be linked to music… painting included. 77 mixed marvelously the ambient sounds created by Eno ex profeso for the presentation with the outstanding images full of colour and life that were appearing at regular intervals in front of all of us sitting inside the dark, very dark room without even realising the presence of the others.

The question I stated above is there because, despite how much I personally admire Eno and his music, it is difficult to me sometimes telling the artistic merit behind something created by computers. 77 was made up by a program designed by Eno himself, which randomly depicted a series of combinations of colour, shapes and shades he already decided in advance. The combinations could ad up to 77 million different depictions (therefore, the name of the exposition that has gone all over the world, and re-designed ad hoc for our country). Now, Eno’s ambient music is entirely made by computer, Eno’s paintings are entirely made by computer… is it still art?

The question I stated above is there because, despite how much I personally admire Eno and his music, it is difficult to me sometimes telling the artistic merit behind something created by computers. 77 was made up by a program designed by Eno himself, which randomly depicted a series of combinations of colour, shapes and shades he already decided in advance. The combinations could ad up to 77 million different depictions (therefore, the name of the exposition that has gone all over the world, and re-designed ad hoc for our country). Now, Eno’s ambient music is entirely made by computer, Eno’s paintings are entirely made by computer… is it still art?

Descartes

Is INCEPTION more than just a movie?

Finally, dreams, as I said earlier, seem to be the most private thing a man can think of. But what would happen if, just like in the movie, dreams could be invaded by others, shared and controlled? The creepy thing in all this matter is that it is not just an issue of science fiction, but a (soon to be born) reality in research at universities all over the USA. The idea of creating artificial intelligence as well as devices that could change come of the settings of our minds forever are things we should worry about. In ethical terms, is it OK to think of the possibility of accessing other people’s deepest thoughts?

If you remember the movie clearly, here are some possible readings of the movie that increase the paradox immensely. Consider them and reflect on them as well:

READING 1: Saito hired Cobb and co. to plant an idea in Fischer’s mind. They succeed, and in the end Cobb really does go home to his kids.

All the levels identified in the movie, make up a series of paradoxical realities that contradict each other but, in the end there is just one thing common to all of them, that is, the token each character holds, that keeps them from being mental, or getting lost. Is there anything in our daily life that actually functions as a token? We need, I reckon something, whatever it is, in our lives that reminds us of who we are all along the way… because how can I know I am the same person I was five minutes or five years ago if I look totally (or considerably) different? What does my singularity and continuity depend on?